Consider the role of a producer in the recording studio. Here are some ways to self-produce and reach higher creative levels

Producers play a pivotal yet enigmatic role in the music industry’s machinations. For those seeking production advice, it’s sometimes hard to pin down exactly what it is that a great record producer brings to the table.

Music producers are often the studio’s alchemists, seamlessly blending insight on musical arrangements and audience expectations one moment and gracefully stepping back the next, allowing artists the space to explore and forge their own path. Sometimes, they also serve as conduits between record labels and musicians, balancing the need for commercial appeal with the creative impulses of the artist. They might even make you a cup of coffee on occasion, or tell you that your song is terrible. Every situation is probably unique on some level.

Some producers, with a keen understanding of the human psyche, excel at navigating the complex web of personal dynamics within a band. They steer the group toward harmonious collaboration while focusing on pragmatic aspects such as budgeting and timelines. A great producer helps spark creativity using the materials the band brings into the studio. For those of us making music alone, one aspect of self-producing is attempting to view such materials as if you are an outsider. It’s a dance, for sure, and this article aims to push you toward a reasonable process that will result in a finished piece of music. That’s the real goal: make a track.

Who was the architect behind The Beatles’ iconic sound?

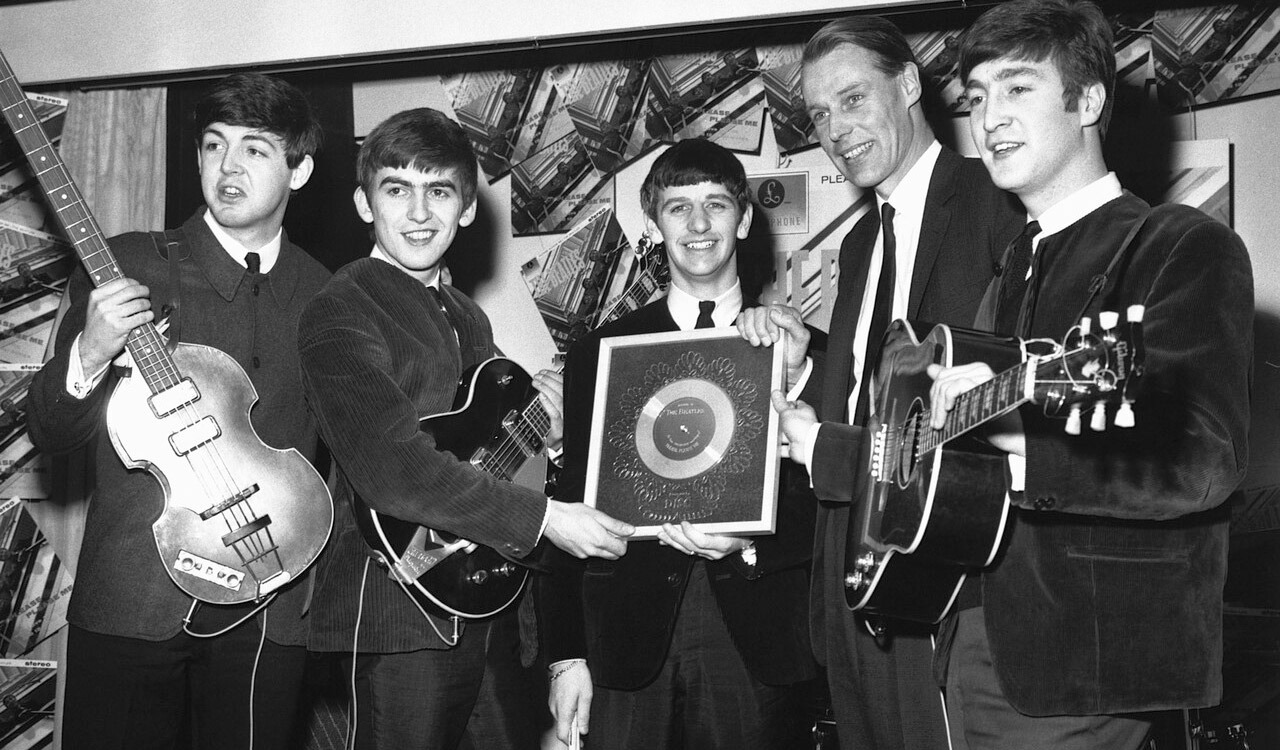

The 2021 Peter Jackson documentary, The Beatles: Get Back, peels back the curtain on the dynamics of music production within a group of highly creative individuals. Yet, even in a room full of musical geniuses, George Martin (later Sir George Martin) emerges as a towering figure, exemplifying the profound impact a skilled producer can have on a final product. Armed with their own musical prowess, producers such as Martin serve as the perfect sounding boards, nudging even the most adept composers towards uncharted territories of innovation.

Martin, often hailed as “The Fifth Beatle,” played an instrumental role in the evolution and success of The Beatles, acting as their record producer, arranger, and mentor. His profound influence on the band’s music was pivotal from their first studio album right through to their last. Martin’s background in classical music, sophisticated approach to music production—and even his experience of making novelty and comedy records—allowed him to translate the band’s more abstract ideas into sonic reality, enabling The Beatles to experiment with more ambitious arrangements and innovative recording techniques.

Martin first encountered The Beatles in 1962 and was initially skeptical of their musical abilities, but he was charmed by their charisma and wit. Recognizing their potential, he signed them to Parlophone Records and began a partnership that would redefine pop music.

In 2016, Sir Paul McCartney had these stirring words to say about Martin’s passing: “He was a true gentleman and like a second father to me. He guided the career of The Beatles with such skill and good humor that he became a true friend to me and my family. If anyone earned the title of the fifth Beatle it was George. From the day that he gave The Beatles our first recording contract to the last time I saw him, he was the most generous, intelligent, and musical person I’ve ever had the pleasure to know.”

Martin’s expertise in orchestration and his adventurous approach to sound production helped create the daring soundscapes that would cement the iconic status of albums such as “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “Revolver,” and “Abbey Road.” For instance, in response to John Lennon’s brief that the orchestra should provide “a tremendous build-up, from nothing up to something absolutely like the end of the world,” it was Martin who arranged the groundbreaking orchestral climax to “A Day in the Life.”

Martin’s willingness to incorporate instruments from outside of the beat-group idiom and to explore the possibilities of the studio as an instrument in itself significantly broadened the expressive capabilities of The Beatles’ music. This helped them evolve from a chart-topping pop group into the most creative and influential act in music history. Martin’s contributions were both technical and deeply creative, fostering an environment where The Beatles could experiment and express themselves musically in ways that no band had before.

Action that leads to results you can be proud of

Like The Beatles, you may sometimes need a producer, too. All it takes is a bit of planning and a willingness to soldier through a process.

Have you ever found yourself in a musical rut, where every chord you play feels as predictable as the last, and new ideas seem just out of reach? The proverbial “writer’s block” for a musician can manifest as a frustrating barrier, where the flow of creativity seems to halt, leaving one unable to produce new material or find inspiration in familiar muses. Does your looper pedal frown at you, knowing you’re about to play the same tired scale over the same tired drone?

This common challenge can arise from various sources—pressure to succeed, fear of failure, or even the repetitive nature of one’s routine—leading to a sense of artistic stagnation. Maybe you are even suffering from option paralysis. The good news is that myriad ways exist to break free from this standstill. A fresh perspective may rekindle your passion for music.

One thing to try up front is to interact with experts to gain a deeper level of knowledge concerning your chosen instrument. If you play guitar, try the Gibson App and seek out the courses that address areas of your own skill that you know are lacking. If you have collaborators, ask them what areas they would appreciate seeing you grow in and find instruction that addresses them. YouTube knows you very well and may suggest something useful, too.

Every budding solo artist is eager for new inspiration. The exercises below encourage you to familiarize yourself with the foundational elements of music that, when creatively pieced together, can guide you towards captivating tracks. The article serves as a production assistant alongside you as the producer. Remember, writing a masterpiece often begins with a single step. Allow your curiosity to lead the way, and let your creativity flourish in its own unique rhythm.

Begin strongly and aim high—read through the entire article so you’ll have a big-picture sense of what this process entails. Think of this as a serious weekend-long project, attempting to stay on course and complete all the steps. Finishing things is what separates amateurs from those intending to continually grow in their skills, and it’s where a lot of the joy of making music really comes from. You want to end up with something you’re proud to share with the world. Also, you want to be engrossed to the point that you experience “flow,” a concept researched and exposited by Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi, a Hungarian psychologist. If you love music, that won’t be a problem.

Get inspired with some drum loops or drum programming

Start with an exciting drum loop, and then find another one you like that is not in the same tempo or style. The web and many music magazines are rife with free choices, and you can certainly buy some great loops, too. Or, invite someone to create a few for you. Plenty of hobbyist drummers and home producers are capable of making stellar loops, and nothing is stopping you from doing this part on your own, either. Get an exciting pattern happening that will set the stage for the next steps. Alternatively, you may have a sound you’re going for, so programming your own patterns might be the best way forward.

Timestretch the second loop to match the tempo of the first and then chop the waveforms and reassemble them into something unusual–stay focused on developing a genuinely addictive groove and keep the idea of “call and response” in mind as you pair the beats up. You may have to learn how to use your DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) more deeply to achieve this, but it will be time well spent.

Alternatively, you can start with two loops already in the same tempo. This may deliver less striking results overall, but maybe beat creation isn’t a highly developed skill for you at this time. That’s OK. The goal is to get going on something with some real inspiration in the foundational drum patterns. Grooving is good, especially initially, and some of the most successful song arrangements of all time have been built around very simple rhythmic patterns.

Then, using percussion samples or a secondary drum plugin, continue layering until you have a part that can be overtly simple at times and more complex for other sections of your piece by turning on/off timbral layers. Don’t be afraid to experiment with glitchy percussion or radical EQ techniques to shape the grooves you are working with—your goal is to produce an exciting set of six or seven customized loops that can be the backbone of the entire work as well as an initial foundation of inspiration.

Many artists start with a simple drum groove and experiment with ideas over it. Keep in mind, too, that toward the end of this compositional process, you will probably need to customize the last measure of some of these loops to make propulsive fills to help tie sections together. Save those crucial details for last! You’ll know what to do when the time comes—after some serious thought has been invested in the arrangement.

If all of this sounds terrifying, don’t panic. Apple’s Logic and GarageBand DAWs both contain virtual drummers in myriad styles with editable kits, sounds, and playing styles. It’s very easy to set up and finesse a groove to your taste, and once you’ve recorded other parts you can even have the virtual drummer follow another track’s rhythm. The results can be extremely impressive and Logic drums have featured on many hit records.

Repetition and memorability are the key techniques for a sticky chorus—and being weird?

For the chorus, create a two-chord progression and active bassline using A minor and E minor chords. Attempt to write three distinct and independent melodies over these two chords, keeping the bass simple unless it will be a huge part of the hook. A smart rule of thumb is to use longer note values to make the melodic line less busy when the drums and bass are busy and vice versa. In doing this, it’s your goal to use repetition as an ally. The more you can make this part feel like a “lift,” the better.

Try to make the melodies expansive, riff-like, and catchy. Try to outdo yourself with each iteration, searching for perfection. You’ll want this melody to be infectious and able to motivate you to continue composing. Use your drum loops from step one to help spice up the process. A tiny push in overall track volume may be appropriate here, too, but it’s too early to start mixing in earnest. It’s usually better to achieve a form and then chisel down into the details.

Gibson signature artist, Rick Beato, analyzes Bowie’s weirdness in the video below. It might prove inspirational.

Pick your favorite of the three melodies you wrote previously and then begin to reverse the playback of the remainder in an effort to create a “foil” melody to stack on top of the main line. This may require some waveform chopping, truncating, and additional research into your DAW, and you may not succeed. This step has some random aspects in terms of ending up with something to integrate into the piece of music, but the history of popular music is full of happy accidents.

Your goal is to discover lines that elevate and support the main melody, and as such, it isn’t a hard and fast exercise of merely reversing things willy-nilly. You need to be ready to mangle the reversed stuff and throw away notes you don’t need because you’re trying to improve things, not blindly add a sonic ingredient.

Using a delay plugin can often lead to extraordinary results. And, of course, ditching this step and writing counter-melodies directly is an option if you hear something in your head—there is nothing wrong with that approach. But there’s often some magic in reversing viable melodies using studio trickery to discover things you may not have thought of initially.

This is definitely a step that involves some chaos and luck, but never just follow a recipe if you feel you have a better idea. It’s your music, and it should substantially reflect you and your decisions.

A reasonable approach to composing the verse section

As you move along, compose another diatonic progression in the same key, but this time use four chords, in this case, use A minor, F, C, and finally G. Block this progression out using a very simple sound like a synth pad with a mild attack.

Then, compose two more melodies over this progression with the goal of having a “stately stated” melodic line that is more of a conversation than a mere melodic fragment. Keep your bassline simple but supportive for this section, taking care to allow pickup notes to propel the groove along.

In the end, you may have a clear favorite among these two and repeat it when your verse section comes around again, or you may choose to use them both as related but individual variations each time the verse chords are used. The point is to not settle for the first thing you do but to strive toward having to exclude material rather than long for it. Better to have material to cut than not enough to keep going strong.

That said, sometimes your first idea might be the best because it’s so instinctive—there’s a reason why many hit records contain lighting-in-a-bottle first takes with an energy and enthusiasm that’s tough to replicate. The beauty of recording music is that there are no hard and fast rules—if it sounds good in the context of the track, it is good.

Does my song need a bridge?

Finally, take the ii chord of this key and integrate it as the last chord in a sequence–in this case, in A minor, the ii is B diminished or B minor seventh flat five (B, D, F, A). So, try F, G, F, B diminished (Bm7-5) as your progression. You may try arpeggiation in spots, a more staccato or syncopated rhythm compared to the other sections, or perhaps you’ll end up orchestrating the notes across several instruments so that the chord emerges from different timbral layers.

Then, compose a plaintive melody that resolves directly to A minor back into the chorus or the verse section. The goal is to create unresolved tension in the melody and chords until it drops back into the A minor chord. This will make the resolution powerful and allow the bridge to be a creative turn from the main parts you’ve already established.

Arrangement is one of the most vital songwriting skills

Lastly, attempt to assemble these various sections into a cohesive whole. Verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, chorus; that might be a decent starting point for the arrangement, but let your own intuition guide you. These days, against the backdrop of hugely competitive and fast-moving social media feeds, many hit records begin with the chorus in order to stand out and hammer the hook home. It also worked for The Beatles back in 1963.

You’ll probably only use the bridge section once, so keep that in mind. It’s connective tissue, though it can be just as creative as any other part of the piece. Still, it functions in a predictable manner as a “palette cleanser,” making the repetition of the other parts more exciting.

Optionally and in addition to the above efforts, you may want to create a solo section for a melodic excursion. Memorable solos deliver listeners right back into the main parts of the song in a dramatic way. Also, your solo can escalate into the bridge if you like, giving that section a functional purpose and a unique build-up.

And there’s never anything wrong with writing a creative intro to help establish the key and give your listener a chance to experience anticipation for what follows. Save that for near the end of the process.

And there you have it: A producer’s abstract guidance to quickly getting a track going in the studio! If you follow these steps, you’ll have created a diatonic composition with quite a bit of effort invested in each part of the piece. Don’t forget to go back through your composition and add drum fills to give some sections more closure and propulsion.

Things to keep in mind

- Do these exercises in a treated room with the best monitors you can afford. We shamelessly recommend KRKs (and the bigger, the better), as you want to monitor all the frequencies in the spectrum if you can. Mixing is about telling the truth about frequencies, to a large degree, and calling attention to things with dynamics.

- Most producers recommend putting some fresh strings on your axe and stretching them thoroughly before you hit the record button. There’s hardly anything worse than a great take with pitch flaws that could have been avoided. However, there’s also a lot of creative mileage in grungy old strings on acoustic guitars if you are going for more of a lo-fi, vintage sound. For vintage bass tones, you’ll also want the oldest and most played-in set of strings you can muster.

- Have a variety of picks on hand to help shape your tone across multiple takes. We have an article on that topic.

- MESA/Boogie has an excellent cabinet emulator to assist with recording your amps.

- Don’t neglect to register your work with a Performing Rights Organization (PRO) to protect your music from theft and secure the legal basis for collecting royalties. Study up on what a “writer’s share” and a “publisher’s share” are—you need to consider both.

What avenues of music composition can I research to elevate this process?

The following are some additional topics to research in your quest to improve your songwriting and production skills. Fire up a Google search or YouTube and soak in some ideas:

- Parallel compression

- Passing chords

- Inversions

- Voice leading

- Modulation

- Submixing, stems, or sub busses

- Syncopation

- Risers

- Impacts (a sampling term)

Recommended reading: “Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience” by Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi

Shop Gibson, Epiphone, and Kramer for fine instruments to weave into the sonic masterpiece you’ve created.