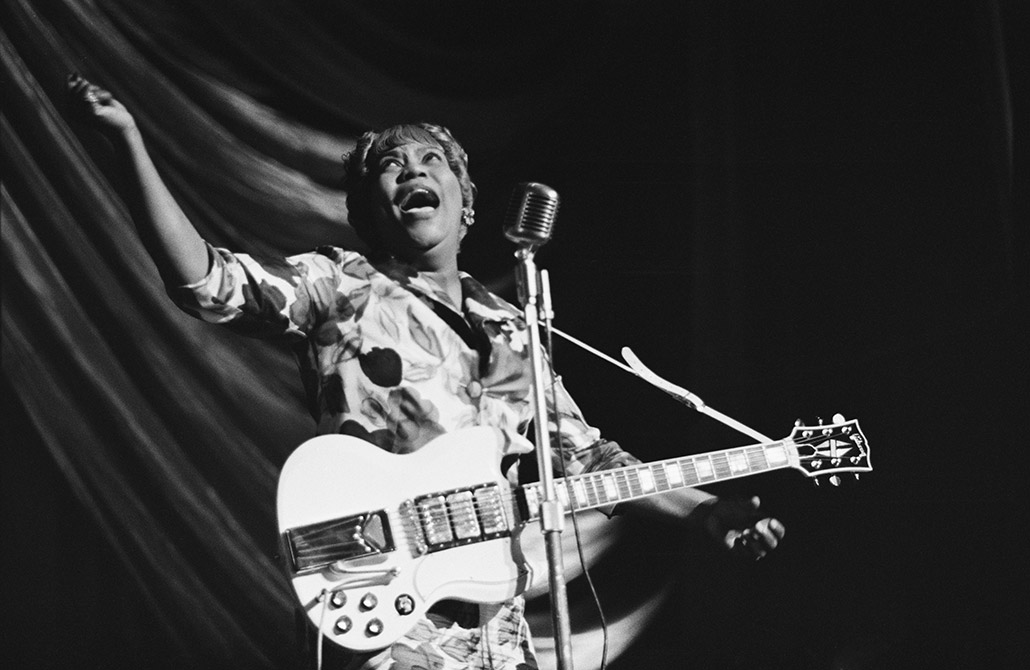

From gospel breakout star to trailblazing R&B guitarist, Sister Rosetta taught the world how to rock and roll

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame has its critics, but arguably no artist was more overdue for recognition than Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Her induction into the Hall’s “Influences” happened in 2018, but it was more than just a victory for rockin’ sisterhood; it was a long-awaited shout to a truly great artist. Don’t know enough about her? Praise be, here’s your guide to the First Lady of Gibson.

Who Was She?

Back in the day, music was even more sliced and diced into categories than it is now. However, if there was one “Gospel” artist who was the genre’s breakout name, the first real crossover superstar, it was Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Sister Tharpe was rockin’ before rockin’ existed—her first hit (and it was even called “Rock Me”!) was way back in 1938 when Elvis was a mere toddler.

She was born Rosetta Nubin in Cotton Plant, Arkansas, in 1915 and was a remarkable prodigy. Rosetta sang gospel in church by the age of six and was soon playing guitar. After moving to Chicago, she headed to New York City, where her musical education exploded. Like a righteous gatecrasher, she began playing at the Cotton Club with Duke Ellington as her teens swung by. She played with Dizzy Gillespie, then with swing bandleader Lucky Millinder. She soon headed back south to tour with fellow gospel icons, the Dixie Hummingbirds.

That first single of hers had come in 1938, and in 1945, her sassy single “Strange Things Happening Every Day”—with its hot guitar solo—was the first gospel single to cross over on the Billboard race charts, what we’d now call R&B. Amid all the claims for the “first rock ’n’ roll record” over the years, “Strange Things Happening Every Day” has as good a claim as any.

The thing is, it remains hard to categorize Rosetta Tharpe’s music as it is varied and broad. Pure gospel, smooth jazz, horn-backed ballads, proto-rock ‘n’ roll jump rhythms, shredding guitar (yes!)—she covered a lot of bases. Her guitar playing was notable, and she was one of the very first players to use distortion, which for a gospel singer, is extraordinary.

Tharpe was a brilliant guitar player, yet almost never acknowledged in the annals of rock ’n’ roll. It shouldn’t be a surprise, even if it’s wrong. The “accepted” tale of rock ‘n’ roll—with Elvis as some sort of fountainhead—is the story of white men, and Sister Tharpe was, of course, neither white nor a man. But, whoa, she could play.

According to fellow gospel star of the day, Inez Andrews, “The fellows would look at her, and I don’t know whether there was envy or what, but sometimes she would play rings around them. She was the only lady I know that would pick a guitar, and the men would stand back.” “She could play the guitar like nobody else . . . nobody!” added Lottie Henry, a member of Tharpe’s backup vocal group, The Rosettes.

And plenty of others were wowed by her. Chuck Berry was a fan (you can clearly hear her influence on his double-stop licks and his songs), so was Little Richard (she was also a brilliant pianist), Isaac Hayes, and Elvis himself was a massive devotee. “Elvis loved Rosetta Tharpe,” attests Gordon Stoker of The Jordanaires, who backed both Sister Rosetta and Elvis. “Not only did he dig her guitar playing, but he dug her singing too.”

Her brief mainstream breakthrough didn’t last too long. Sister Rosetta saw her gifts as given by God and—although remarkably innuendo-laden and sassy often-times—she broadly stayed within the confines of “church music” as a whole and forewent the secular moves of the rock ‘n’ roll explosion. She was also unfortunate to be around at the same time as the phenomenal Mahalia Jackson.

Tharpe knew, though: in 1957, when asked where she fitted into this new music, she replied: “All this new stuff they call rock ’n’ roll, why, I’ve been playing that for years now . . . Ninety percent of rock ’n’ roll artists came out of the church, their foundation is the church.”

Like many African-American artists of the pre-rock ’n’ roll era, she re-emerged into the spotlight via the UK. In 1964, as the folk revival peaked, she was booked for the Folk Blues and Gospel Caravan tour in England (alongside Muddy Waters, among others), and she played a famous gig in an abandoned railroad station staged by Manchester’s Granada Television.

Although a typically rain-soaked day in Northern England, Tharpe made the most of her slot by arriving in a horse-drawn carriage like royalty, strode across the wet platform in “Chorltonville” (actually Chorlton, a district of Manchester), picked up her Gibson SG Custom and belts out “Didn’t It Rain”—any electric-shock risk and tuning problems be damned! It’s genius. “I’m sure there are a lot of young English guys who picked up electric guitars after getting a look at her,” said Bob Dylan, another disciple of Sister Rosetta.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s music periodically gets a boost back into the spotlight. Gayle F Wald’s 2007 biography, Shout, Sister, Shout! certainly helped: “When you see Elvis Presley singing early in his career . . . imagine he is channeling Sister Rosetta Tharpe,” Wald has suggested, “It’s not an image I think we’re used to thinking about when we think of rock ’n’ roll history—we don’t think about the black woman behind the young white man.”

A stage play of the same name has been running across various US theaters since and is great: compilations keep coming, but there is no doubt Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s HOF induction placed her rightfully back center-stage. For Bonnie Raitt, Sister Rosetta “blazed a trail for the rest of us women guitarists with her indomitable spirit and accomplished, engaging style. She has long been deserving of wider recognition and a place of honor in the field of music history.” An “Influences” badge at her Hall of Fame ceremony sufficed: but others may prefer a sobriquet that has also been given to Tharpe: the “Godmother of Rock ’n’ Roll!”

Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Gibson

Sister Rosetta played plenty of models over the years, but her go-to’s were Gibsons—a Gibson Barney Kessel, a 1952 Gibson Les Paul Goldtop, and the 1940s Gibson L-5 acoustic you’ll see in the film short Shout Sister Shout. She also played a Gibson ES-330TD thinline with P-90 pickups (at the 1967 Newport Folk Festival) and, most famously, an early-60s Gibson SG Custom with sideways Vibrola (just like Mary Ford’s). Her playing style was unorthodox for a soloist—she used a thumb pick, revealing her roots in acoustic blues.

There’s no recent Gibson out there exactly like Tharpe’s—2015’s Gibson USA SGS3 was a close spec (but is in Ebony), while Gibson Custom’s white SG Custom has a Maestro Vibrola, not the sideways version. Gibson currently offers a variety of memorabilia celebrating Rosetta Tharpe here.